Plate, probably Staffordshire (manufactured) and Liverpool (printed), England, ca. 1778. Creamware. D. 9 3/4“. (Courtesy, Reeves Museum of Ceramics, Washington and Lee University; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the plate illustrated in fig. 1.

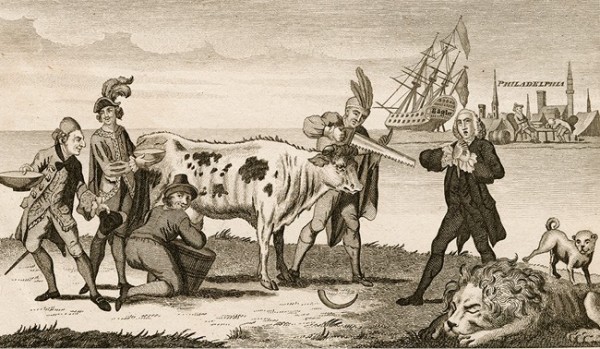

A Picturesque View of the State of the Nation for February 1778, illustrated in Westminster Magazine 6 (March 1, 1778), p. 66. Engraving. 4 x 6 13/16”. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.)

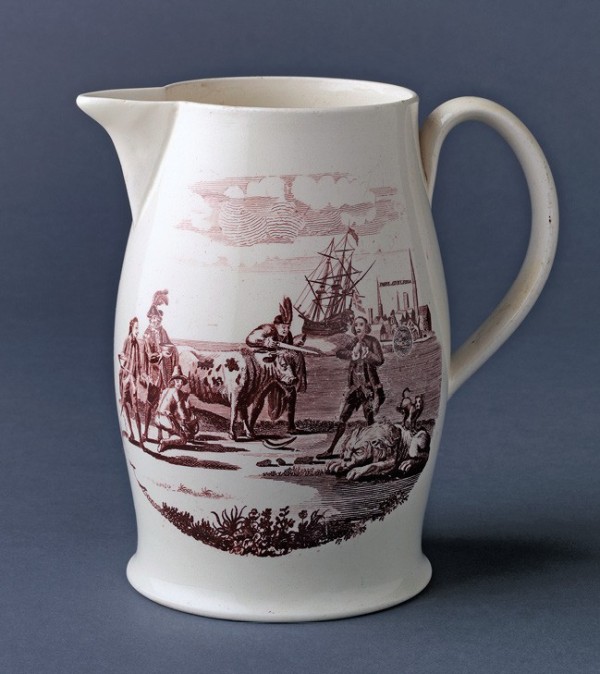

Jug, probably Staffordshire (manufactured) and Liverpool (printed), England, ca. 1778. Creamware. H. 6 1/2“. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

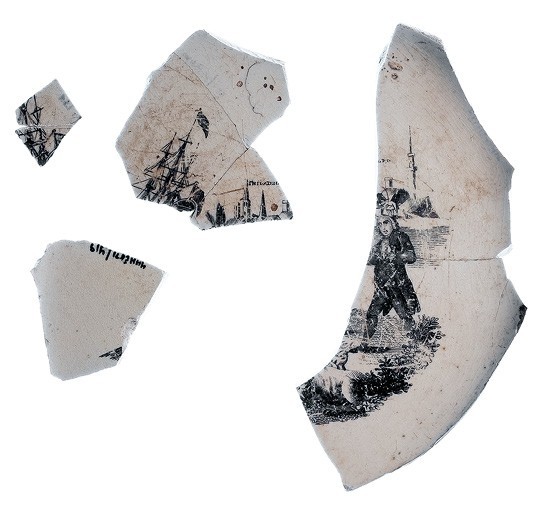

Fragments of two plates, probably Staffordshire (manufactured) and Liverpool (printed), England, ca. 1778. Creamware. H. of largest fragment 6". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments were recovered from Lot #203, Rocketts Landing, Richmond, Virginia.

Aerial view of the excavation of Lot #203, Rocketts Landing, Virginia, ca. 1992. (Photo, courtesy of Dan Mouer and Jolene Smith.)

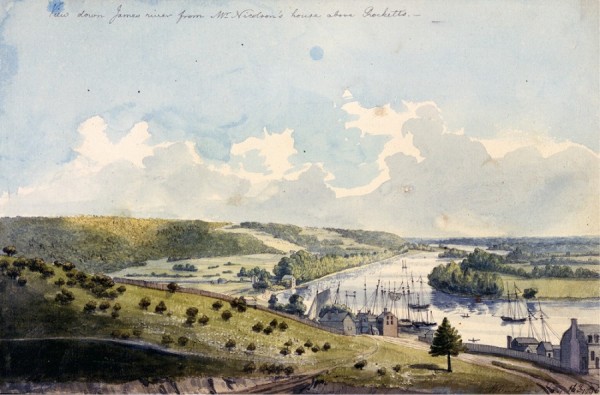

Benjamin Latrobe, “View down James River from Mr. Nicolson’s house above Rockett’s,” May 16, 1796. Watercolor on paper. 10 1/2 x 7". (Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture.) This view was captured from the home of a “Mr. Nicholson” as Latrobe looked out at the winding James River and the growing trading village and port known as Rockett’s Landing, or simply “Rocketts,” in Richmond, Virginia.

Fragment of a vessel, probably Staffordshire (manufactured) and Liverpool (printed), England, ca. 1778. Creamware. H. 2 1/2“. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) This fragment, probably of a plate, was recovered from the site of the National Constitution Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Corner of Hoffman’s Alley and Quarry Street, 1931. (Courtesy, City of Philadelphia, Historic Commission.) The plate was found in a privy behind the house on Hoffman’s Alley, just visible on the left behind the row of five tenements.

Profile view of the partially excavated privy from the National Constitution Center site that contained the plate. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) This photo shows multiple trash layers containing eighteenth-century ceramics, glass, and other household trash. The scale across the top of the deposit is five feet in length.

ONE OF THE EARLIEST American subjects to appear on English transfer-printed earthenware is “A Picturesque View of the State of the Nation for February 1778,” a political cartoon deploring the failure of British forces to pacify the rebellious American colonies and the devastating effect the Revolutionary War is having on British trade (figs. 1, 2).

The rather complex allegorical image shows British commerce as a cow whose horns are being cut off by an American in a feathered headdress. Robbed of her defenses, the cow is being milked by a Dutchman while a Frenchman and Spaniard look on with anticipation. A British merchant wrings his hand in distress while, adding insult to injury, a French pug dog urinates on the back of a sleeping British lion. In the background, William Howe, commander in chief of the British forces in America, and his brother Admiral Richard Howe, commander of the Royal Navy’s North American Station, sit slumped over a punchbowl before Howe’s flagship, HMS Eagle, which lies beached before the city of Philadelphia.[1]

The cartoon was first published in Westminster Magazine in March 1778. Clearly it struck a chord, for it was quickly republished several times in Britain as well as in Netherlands and France (fig. 3).[2] An enterprising English potter or merchant, many of whom were suffering from the loss of their American markets and no doubt sympathetic to the cartoon’s message, copied the image onto jugs and plates (figs. 1, 4).[3]

The assumption has been that the creamware pieces decorated with the cartoon were made for British sympathizers, and that disruptions in trade and the blockade of American ports would have prevented such pieces from reaching America. However, two plates found in Richmond, Virginia, and a third found in Philadelphia suggest that examples did make it to America and were available to patriotic consumers.

Two plates were found at Rocketts Landing, the principal eighteenth- and nineteenth-century port for Richmond, Virginia (figs. 5, 6). Robert Rocketts operated a ferry across the James River just east of Richmond as early as 1730, and it is from that landing that the community took its name. In the decades before and after the American Revolution, Rocketts was a community of substantial brick houses, frame houses, warehouses, and workshops that were home to people of different ethnicities, nationalities, and trades, including British, African, and American-born merchants, sailors, artisans, plantation owners, and enslaved laborers. As the westernmost navigable point on the James River, Rocketts was well placed to receive goods imported from Britain and other ports in Europe and the Americas (fig. 7).[4]

The fragments of the two plates were found on a lot thought to have been associated with merchant John Hague (ca. 1758–1795), who might have been their original owner.[5] Hague was one of many merchants who dominated Richmond, and particularly Rocketts, both socially and economically in the eighteenth century.[6] In 1790 he was described as a merchant who “owns a wharf—is engaged in some little traffic—& is concerned in river craft or two. . . .”[7] Despite being a British native, Hague seems to have supported the American cause and the new nation, serving as a state customs searcher from February 1781 and still serving in that capacity in 1794. He was considered for the federal office of collector of customs for Richmond in 1790.[8]

Another possible original owner of the plates is John Craddock, John Hague’s nephew (or perhaps his wife’s nephew), apprentice, and later business partner. Craddock served in the Continental Navy and was even a captive of the British for a short time. He is known to have been in Philadelphia in 1779, when he received a disbursement from the city’s public stores, so he could have purchased the plates then.[9]

A third piece with the same design, most likely a plate, was found in Philadelphia (fig. 8), excavated at the site of the National Constitution Center at Independence National Historical Park. It was recovered from a privy along with more than four thousand other ceramic artifacts on a lot between 5th and 6th and Cherry and Race streets that was owned by merchant and land speculator Caleb Cresson (1742–1816).[10] Cresson built a rental-housing and business empire on the block, including two small dwellings with privies on Hoffman’s Alley, just beyond the wall of his own large home at the corner of the alley and Cherry Street. It was from the southern privy behind these two rental houses that the fragment was recovered (figs. 9–10).

While it is not known who lived in the house during the 1770s and 1780s, Cresson’s tenants generally consisted of middle- and working-class men and women, both black and white, some of whom were American-born, and others were immigrants from Europe. The rate of tenant turnover was high, further complicating attempts to identify individual residents who may have owned this plate.[11]

We might never know who owned the plate, but it is likely they were American patriots who survived not only the Revolution, but also the British occupation of Philadelphia. Interestingly, among the artifacts from Cresson’s own privy next door were a number of military objects—two muskets, swords, shot, and regimental buttons—that suggests that his home, and likely the rental houses around him, were occupied by the British during their stay in Philadelphia from September 1777 to June 1778. The irony of the plate appearing on the very site where British officers and their troops may have been quartered is profound, and further illustrates the importance of objects in conveying ideas, taste, and, as here, political messages.

S. Robert Teitelman, Patricia A. Halfpenny, and Ronald W. Fuchs II, Success to America: Creamware for the American Market (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2010), pp. 68–69.

E. McSherry Fowble, Two Centuries of Prints in America, 1680–1880: A Selective Catalogue of the Winterthur Museum Collection (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1987), pp. 167–68.

Teitelman, Halfpenny, and Fuchs, Success to America, pp. 68–69. A number of examples are known, including two jugs and a plate in the Winterthur Museum (1958.1201, 2009.21.21, and 1999.38.1, respectively), a cream jug in the Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove, England, and plates at Historic Deerfield (2009.24), the Reeves Museum of Ceramics (2019.21.1), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1935.105.1). A platter is in a private -collection.

The plates were recovered from Lot #203, Rocketts Landing (Site 44HE0671). L. Daniel Mouer, Rocketts: The Archaeology of the Rocketts Number 1 Site (441 He 671), lot 203 in the City of Richmond, 3 vols. (Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University, Archaeological Research Center, 1992), 1:304–5.

Hague was living “near Richmond” on May 24, 1776, when he placed an ad in the Virginia Gazette hoping to recover a lost horse. He is thought to have begun leasing the property in the 1770s and may have constructed a “dwelling house” and “lumber house” or storage building on the lot around the time of the American Revolution. The lumber house was destroyed about 1780–1781, perhaps during the British occupation of Richmond. By 1788 Hague owned the property outright and lived there until his death in 1795. Afterward, his widow, Hannah, inherited an interest in the property, which ultimately descended to the testator’s nephew, John Craddock. Henrico County Will Book 5 [1796–1800], pp. 187–88. The fragments of the two plates were recovered from several features dated to the 1810s and 1850s, but it is thought that the plates were broken and thrown away prior to the construction of a large lumber house or warehouse built on the site about 1795. Mouer, Rocketts, 1:304–5; Alexander Purdie, Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg), May 24, 1776, p. 2, col. 1.

Mouer, Rocketts, 1:305.

“From George Washington to Alexander Hamilton, 27 September 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-06-02-0237. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 6, 1 July 1790 – 30 November 1790, edited by Mark A. Mastromarino (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996), pp. 514–15.

Ibid.; William P. Palmer, Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 11 vols. (1875–93; reprint, New York: Kraus Reprint Corp., 1968), 4:228, 235; 7:238, 367.

Mouer, Rocketts, 1:306.

The artifacts were discarded into the privy sometime in the early 1790s, as indicated by the manufacture dates of the English ceramics found in it. The abundance of ceramics, which appear to be a mix of used and new types and forms, suggests that the site was used as both a home (based on the amount of use wear on some of the vessels) and possibly a store or small warehouse. The latter hypothesis is based primarily on twelve china glaze pearlware punch bowls of various sizes, all of which are broken in the same manner, as though they had been stacked within each other and fell off a shelf. The decoration of the punch bowls also implies they were decorated by the same hand and likely came from one shipment.

For more information on Cresson, his tenants, and housing spatial relationships in the late eighteenth century, see Deborah L. Miller, “‘Great Earthly Riches Are No Real Advantage to Our Posterity . . . ’: Space, Archaeology, and the Philadelphia Home,” in At Home in the Eighteenth Century: Interrogating Domestic Space, edited by Stephen G. Hague and Karen Lipsedge (Oxfordshire, Eng.: Routledge, 2021), pp. 174–98.